This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

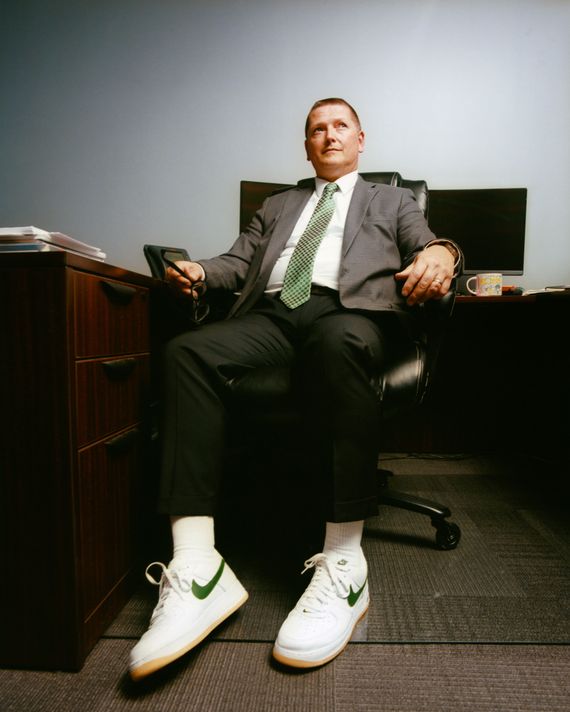

Tom Gibbs first heard the term Rutter from his wife, shortly after they moved to Athens, Ohio, in 2011. A local used it casually during a conversation, and his wife had asked what it meant. Gibbs didn’t know.

In 2013, Gibbs was named associate superintendent of the local school district — where the word seemed to be everywhere. Inside Athens High, the district’s only high school, it rang through the canteen and skipped off the lockers. In one-half of the school, there were the jocks, the geeks, the potheads, and the art kids — all the usual groupings found in big and small towns across America. In the other half, there were the Rutters.

They were the kids who packed snuff in their lips and skipped class to go hunting. They smelled of fire pits, box dye, and the last cigarette they smoked, sucked down before the bell in the last bathroom stall where the lock was broken. The Rutters, it was said, didn’t go to college, because they had no use for a good education.

At least, that was the story Gibbs heard when he arrived. “I was appalled when I first moved here,” he told me. “It was glaringly obvious that there are extreme differences in the populations.”

At Athens High, the Rutters ate in their own section of the cafeteria. They had their own classes, their own quadrant of the school parking lot, their own parties on the weekend. In a nation of systemic racial inequities, the divisions in Athens were not about skin color: 86 percent of the student body was white.

Gibbs gradually pieced together the conditions driving the divide. Athens County lay in an overlapping sliver between Middle America’s two great declines: the manufacturing collapse of the Rust Belt and the shuttered coal mines of central Appalachia. But the school district also contained the city of Athens, home of Ohio University, the largest employer in the county, serving some 30,000 students. Its leafy main campus blends into the city’s historic Uptown area, where brick-lined streets are filled with shops, bars, and restaurants. “The city of Athens itself is in fine shape,” said Gibbs. “But get a few minutes out of town and it’s a different story.”

Once, the Rutters were just one of the dozens of coal-mining families in the area. But sometime after World War II, the name transformed into a kind of slur. Across three decades as an educator, Gibbs had seen plenty of sorting and labeling in school districts up and down the state, but even so, he had never encountered anything quite like this — an underclass distinct enough to spawn its own name.

After settling into the job, Gibbs began to wonder if there was anything that could break down the school’s entrenched barriers. By the time the students reached ninth grade, he realized, it was already too late. So he began to look earlier, to when the kids first entered the school system.

When Gibbs took his post, there were four elementary schools in the Athens City School District. The differences among them were extreme. The professors at Ohio University tended to send their kids to East Elementary, a short walk from campus. At East, hardly any students qualified for free or reduced lunch, a rate reflecting the student body’s family income levels. At two other schools — Morrison-Gordon Elementary and West Elementary — rates were a bit higher, hovering around one-third. But at the Plains Elementary, a ten-minute drive outside Athens City, the number was roughly 75 percent. That was the Rutters’ school.

Within the district, it was an open secret that where the children went to elementary school determined their academic outcomes. Tom Parsons, a former English teacher who came to the district in the ’80s, told me it was easy to rank the schools by performance: It was Plains at the bottom, then West, then a near tie between Morrison and East for the top. “That was it,” he said. “Your future was already there.”

Tammy Hogsett, a former instructor at the Plains Head Start, worked with children who lived in a trailer park wedged between the attendance zones for both the Plains and West Elementary schools. Their families wanted to send their kids to West, yet almost without exception, it didn’t happen. Parents would say their kids weren’t “good enough” to go to West. They told Hogsett, “Because we’re living on assistance, we’re living in a trailer park, we get food stamps, we have a Medicaid card — so our kids aren’t going to be accepted,” she told me. They knew the other families would only view them as Rutters.

Hogsett recalled a meeting with the parents of two young boys. The father wanted his children to have a good education, and West was his dream. But after he left the room, the children’s mother, who had earlier been quiet, shook her head. “I know they’re not going to West,” she said.

In the end, the two boys went to the Plains.

After Gibbs was promoted to superintendent in 2015, he assembled a steering committee to look at the possibility of restructuring the elementary schools to address the district’s socioeconomic disparities. “I’m not saying I have the answers,” he told me, “but shouldn’t we at least talk about it? Shouldn’t we try to experiment with ways to bridge this gap?”

In the winter of 2016, the committee members announced three proposals, all involving combining two or more schools. But the one favored by the majority of committee members involved a complete reset: scrapping the four existing elementary-school buildings and bringing all of the district’s children together in a single, integrated campus.

Opposition to the plan arose immediately. David DeWitt, then an editor and reporter for the Athens News, told me he had never covered an issue that so animated, or divided, the community. “The whole city is really drawing lines and picking sides,” he said. “I’ve never seen signs in yards for an issue that’s not even on the ballot.”

Jenny Klein, a mother of three and an academic adviser at OU, emerged as one of the loudest voices on the side opposing the single campus. In early 2017, I met with her at her house, which is a short walk from East Elementary. Two of her older children had graduated from the school, and her youngest daughter was a kindergartner there — she had recently sung in the East school play.

Klein told me she had learned about the term Rutter more than a decade earlier, shortly after moving into town. One day, her eldest daughter had come home from school and said her hair looked scrambled — like “a Rutter bun.”

“What?” said Klein.

Later, a friend of Klein’s who had lived in Athens for many years told her the term “essentially means dirty, uneducated, messy.”

Klein, like many of the anti-consolidation parents I spoke to, said it was a good thing that the district’s long-standing inequities were being discussed. “We all agree that integration is important,” she told me. “But it would be nice if we could do it without leaving four empty shells of schools and busing everybody all the time.” She was worried too that her youngest daughter, Mackenzie, would get shuffled through the school without the ability to form relationships with all of her teachers and classmates. “You’re going to shake her up like a Yahtzee cup every year,” Klein said.

On the other side, parents and locals who supported the single campus felt that the arguments against it amounted to a defense of entrenched privilege. “Change is difficult,” a steering-committee member told me. He pointed out that many of the plan’s most outspoken critics lived in the neighborhoods surrounding East Elementary. “These people don’t have a bad will,” he said. “They just don’t want to give up what they’ve got.”

In the spring and summer of 2017, the fight over the single campus started to dominate the school board’s monthly meetings. During one meeting in July, Yi-Ting Wang, a local parent who supported the single-campus proposal, took the podium inside the Athens High auditorium. Born in Taiwan, Wang had come to the U.S. on a Fulbright scholarship to study English literature. She met her husband in graduate school, and the couple moved to Athens in 2004 after he received an offer to teach at OU. The years passed quickly: There was a baby, a mortgage, a second daughter to join the first. After their kids got older and began to attend East Elementary, Wang was struck by the school district’s imbalances. She saw that East supported by far the most programming and extracurriculars — from cross-country to drama club to the new LEGO team that her younger daughter loved. Such opportunities were fewer at Morrison and West, and the Plains hardly had any.

When Wang came out in favor of consolidation, she knew she was going against many of her fellow parents at East. In the local Facebook groups, she lost track of the times other parents brandished their university degrees or a barrage of research citations to discredit any comment she made. “When you stand with the poor,” she told me, “you get punished. You get dirty eyes when you pick up your kids.”

She could feel those eyes on her now as she stood and addressed the school board. One of the main obstacles to reform, she told the board, was the political opposition mounted by influential parents who felt that their advantages were being threatened. She cited Jeannie Oakes, a former education professor at UCLA, who had recently told The Atlantic: “It’s difficult for school districts to resist the pressure that comes from white, liberal parents with university credentials. These parents come with such authority.”

Small lines formed behind microphones on each side of the auditorium. The board meeting soon entered its third hour. A tall, thin woman with wispy white hair introduced herself as Barbara Stout. “I myself do not have any children, so you can say I don’t have a horse in this race,” she began. “Except for I do. I’m a member of this community. And I passionately, passionately, passionately believe that the education of all of our children is essential to living in a society that I want to live in.”

Stout had grown up in Athens and attended East Elementary in the early ’60s. When the Athens City School District was established around that time, hers had been among the first classes to graduate from the newly combined high school. “They brought in all those kids” from outside the city, she said. “I can tell you that by the time you get to high school, those barriers are pretty cemented. They really are. Even by junior high school, they’re pretty cemented.”

A woman named Bev Drake was the last to speak. “The kids from the Plains don’t get a fair shake,” she said. “When there’s something that goes on, it’s these kids that get in trouble. It must be their fault because that’s where they come from.”

Drake, an Athens County native, had lived in the Plains for over 40 years. Her three daughters had all graduated from the Plains Elementary. Inside the auditorium, she sighed into the microphone. “We’re a small community,” she said. “We’re not consolidating in my mind. We’re making our system better.” She looked hard at the school board. “It’s time we do this.”

After she got married, Tammy Hogsett, the former Plains Head Start instructor, adopted her husband’s surname, but before that she was Tammy Conner, the oldest daughter of David Conner, a self-employed cement mason, and his wife, Bonnie Conner — whose maiden name was Rutter.

When Hogsett was a young child growing up in Glouster, 15 miles north of Athens, hearing someone say Rutter within the house simply meant that they were calling to one of her aunts or uncles or maybe her grandmother. But once she started school and began meeting new people — not just the other kids but the teachers, too — the meaning of the word transformed.

Hogsett learned that to be a Rutter was to be dirty and smelly and poor and trashy, to be a thief and a cheat and a liar, to be lazy, to not clean your yard or clean your house, to dress poorly, to not be like the other kids, to be less than the other kids, and she came to realize that her association with the name was to be her darkest and most shameful secret.

She was terrified of being found out. One day in middle school, she was walking with a group of friends when they passed another boy in the hallway. He was disheveled with messy hair and shabby clothes. One of Hogsett’s friends pointed at him and said, “Look at that dirty Rutter.”

Hogsett, who didn’t want her friends to suspect anything, laughed along. Afterward, she felt sick. She knew that if her mother ever found out, she would be so sad — not angry, because Hogsett rarely saw anger in her mother, but sad because she saw a fog covering her mother that never lifted.

Hogsett loved her mother. When she was little, her nickname was “Bonnie’s Little Shadow”: She never left her mother’s side. Bonnie Rutter was beautiful and intelligent and compassionate; she could see the good in anybody. But Hogsett witnessed other aspects of her mother, and they, too, became her inheritance. Bonnie’s behavior could be defensive and volatile, wound so tight that the rest of the family found it suffocating. She hated to be seen in public, avoided taking photos, ducked socializing whenever she could.

Anywhere she went, Bonnie felt judged. She would take the kids to McDonald’s, which was for her kind of people, but never to Applebee’s. She wielded a fierce, defensive pride in order to protect whatever could be salvaged. One winter, the family’s concrete business was struggling and Hogsett’s parents had to fill the gap with food stamps. Her mother refused to enter any of the local stores, so for months the kids packed tight into the backseat for the hourlong drive to Vienna, West Virginia, where no one would recognize them. Bonnie always felt the eyes of the world on her.

Her mother’s shame followed Hogsett into adulthood. Hardly a week would pass where Hogsett didn’t hear someone dissing on the Rutters, like when the dollar-store clerk said, “Watch them Rutters over there, they’re probably tryna take something,” or when a new co-worker said, “I live on my own, so it don’t matter if my bathroom looks like a Rutter used it”; or, at 17, when she visited her future mother-in-law’s house for the first time to be greeted with, “Sorry about all this stuff laying around; it’s like a Rutter’s house in here.”

Even as the debate over school consolidation intensified in Athens, Hogsett wondered if any of it would matter.

A few weeks after the school-board meeting, I visited Bev Drake at her house in the Plains. It was late on a Friday afternoon, and she offered me a drink, then poured one for herself. The high school’s football team was playing that evening, and she was heading over later to watch.

Drake told me that she had grown up in Trimble Township, another of southeastern Ohio’s coal towns, a lesser star in the orbit around Athens. She went to Trimble Local Schools, and even back then, they all knew to steer clear of the Athens crowd. They were the children of professors and doctors and attorneys, kids who played ball on nicer fields and liked to talk down to you.

But Drake got her real education in prejudice after becoming a mother. She had moved to the Plains by then and was raising three kids on her own. Those were difficult years: relocating to a trailer court, struggling to support her family with her staff salary from the local hospital, only ever buying work outfits because she couldn’t afford more than one set of clothes. She would never forget the way some parents avoided her eyes, the forced pitch of their smiles, the curt politeness as they gave excuses for why their kids could no longer be her daughters’ playmates.

When her daughters entered grade school, she was dismayed by the state of the Plains Elementary building. One afternoon, following a hard rainfall, she rushed from work to pick up her girls. When she stepped down into the school’s basement classroom, the sight stopped her in her tracks. The teachers had told her that water sometimes leaked in through the paving brick, but here she was, ankle deep in four inches of water. A television set had been wheeled out on a metal cart, and all the kids sat around with their feet pulled up onto their chairs. For a moment, Drake was struck dumb. Then she recovered and began shouting: “Get out of here! All you kids get out! Do not touch the television!”

Drake and several other Plains parents began to organize, eventually registering a group with the county Board of Elections. Their goal was to put a levy on the ballot for a new school building, and they called themselves the ABCS committee because that’s what they were fighting for — a Better Chance for Students. They threw fundraisers. They recruited teachers. They knew they were the underdogs, and they created enough belly-aching from the Plains that the school board in Athens could no longer ignore them.

When a new Plains Elementary opened in 1990, Drake savored the grass-roots victory. “It made you feel a bit like you’re worth something,” she told me. Yet instead of shrinking the distance, the stratums in Athens only seemed to pull further apart. After Drake’s children arrived at the middle school, it didn’t seem to matter that they came from a new school building with upgraded facilities and more resources. They still came from the Plains — and they were still seen as the Rutters. One day in class, one of her daughter’s classmates didn’t know the answer to a question. The teacher snapped back, “Well you went to the Plains, so I wouldn’t expect you to.”

Rusty Rittenhouse, an attorney in Athens, began his term on the school board in 2016. Before the whole controversy over consolidation began, he recalled meetings that lasted, consistently, between 13 to 15 minutes. “It was easy,” he said. “It was business as usual.”

The consolidation debate changed all that. While the other board members seemed to waver on the best path forward, Rittenhouse didn’t hide his support for a single campus. A native of the area, he had heard the term Rutter his whole life; as an adult, he refuses to utter it. “It’s a hurtful word,” he told me. “I would love for that word to be banished.”

At a special school-board meeting in August 2017, Rittenhouse pushed the other four members to disclose the configuration they favored. To his surprise, all but one of them expressed a preference for the single-campus plan. Not long after, I sat with Rittenhouse on a green bench inside the high school’s atrium. Photos of past valedictorians hung from the walls; the hallways were dim and silent. “Has there ever been — at least in this community — a greater cause to fight for?” he asked.

Then the plan fell apart. Gibbs had previously secured an eight-acre plot of land from OU to use for its new facilities. The administration consulted with two different architects; both confirmed the size of the land would be sufficient for roughly 1,500 students — within striking distance of the district’s elementary-age population. But in September, a third firm, Schorr Architects, told the school board that such a configuration would require approximately 20 acres as well as an additional access road at a minimum cost of $1 million.

Gibbs went back to the university to ask for more land. At the October school-board meeting, he reported that his request had been denied. Rittenhouse was gutted. “It was extremely disappointing and frustrating,” he said.

One by one, the board members conceded that the single-campus option was dead. Another board member, Kim Goldsberry, had previously floated an alternative option in case the single campus failed to achieve enough public support. She proposed closing West, distributing kindergarten–to–third-grade students between East and Morrison-Gordon, and moving grades four through six to the Plains.

Without better options, the board coalesced around the new plan, formally endorsing it in a spring 2018 vote. That summer, board members voted unanimously to approve a $60.5 million bond to help pay for the new facilities. The funds would be drawn from a new property tax to be placed on the ballot in November. In the end, the consolidation would be up for the voters to decide.

Because Goldsberry’s plan was less polarizing, Rittenhouse hoped that the tax might have a better chance of passing. When the debate centered on the single campus, “there was no compromise at all,” he said. “I would walk down the street, and people would stop me. You’re an SOB if you do it, and you’re an SOB if you don’t do it.” Yet even as that plan had crumbled, the district’s animating divisions still remained. The gravity of what was at stake weighed on Rittenhouse. “We have one shot right now to heal these deep wounds that exist,” he told me. “It may be one shot for a generation.”

As the vote approached, Gibbs made a final push. At a crowded town-hall meeting, he met with parents and residents. After answering questions on tax levies and configuration details for over an hour, Gibbs took the microphone to close.

“I know a lot of people in the room, but a lot of people in the room don’t know much about me,” he said. “Neither of my parents graduated from high school. I grew up very poor. We moved a lot. But I am here today—having earned three college degrees, earning a good living for my family, providing a different life for my daughter — because there were adults in my life who cared. And they cared by supporting public schools.” He went on, “I hope that all of us in this room — all of us in this school district — can continue to be those people for the children in our lives.”

On Election Night, Gibbs was at the Board of Elections office, following the results as they came in. Sean Parsons, a newly elected school-board member, stopped by to check in. When early reporting looked promising, Gibbs, who rarely showed emotion, came over and hugged him. Parsons had never seen him so excited. In the end, the levy passed with 54 percent of the vote. Within Athens, the only precinct where the measure failed to get a majority was in a cluster of households adjacent to East Elementary.

Renovations of the school facilities began in December 2019, continuing through the many setbacks resulting from the pandemic. For Gibbs, the period provided a recurring reminder of the disparities in his district. When wealthier parents couldn’t understand why they shouldn’t start online learning immediately, he tried to explain that not every household in the district has a computer at home, or a quiet space to study, or a reliable internet connection.

The same thing happened when schools reopened, after five of the district’s bus drivers tested positive for COVID in the same week. Without transportation, Gibbs knew that a third of the district’s students would be unable to attend school. He announced a one-week closure, and immediately the flood of calls and emails started again.

“Why are we closing?”

“Why can’t we just drive our own kids?”

Gibbs explained that not every family has a vehicle at home, or a flexible work schedule that allows parents to drop off and pick up their kids, or even the gas expenses for extra trips into the city each day. “It’s a level of just having blinders on,” he told me.

In the spring of 2021, the remodeled elementary schools were almost ready for in-person classes. Gibbs took out a map and began the task of redrawing school-zone lines. Taking U.S. Route 33, which cut through the middle of Athens City School District, he converged the existing pre-K-to-third-grade populations from the Plains and Morrison-Gordon school zones — south of the highway — into the new Morrison-Gordon Elementary. At the same time, he combined the households in the more concentrated pockets of poverty outside Athens City — north of 33 — with the previous East and West attendance areas into a new school zone for a rebuilt East Elementary.

Gibbs knew that it was the district’s wealthiest households, many of whose members had voted against the levy, that could ultimately determine whether the changes would succeed. “Educated middle-class parents are more likely to be involved in their children’s schools, to insist on high standards, to rid the school of bad teachers, and to ensure adequate resources — in effect, to promote effective schools for their children,” wrote Richard D. Kahlenberg, an education and housing policy consultant, in his 2001 book, All Together Now: Creating Middle-Class Schools Through Public School Choice. The key was a threshold level of socioeconomic integration at which studies have shown, reliably, poor students can benefit without adversely affecting the better off. “Most researchers,” Kahlenberg wrote, “have converged around the 50 percent mark.”

After he finished redrawing the new school lines, Gibbs spent hours hunched over his office table, hand-checking individual names to ensure the district’s free or reduced-lunch students were equally distributed between East and Morrison-Gordon. When they formally reopened in the fall, the proportion at each school stood at exactly 37.1 percent.

In the fall of 2021, I met with Jenny Klein, who had helped lead the opposition against the consolidation campaign. Her youngest daughter, Mackenzie, had recently entered fifth grade. When COVID moved classes online, Klein had set up a pod with other neighborhood parents and hired a college student to work with Mackenzie one-on-one. “She learned a ton,” Klein said.

Yet even as her own family weathered the pandemic, Klein mourned what had been taken away. Previously, at East, her two older girls had gotten to participate in an endless stream of school programming. “You were always getting a flyer home,” she recalled. “Every time I turned around, there was a winter festival, an ice-cream social, a dance, a reading, a book fair.” After the consolidation, she said, there was a drastic reduction in extracurriculars and no more “sense of belonging.” Part of this was likely due to the pandemic. But when Klein shared her concerns at a PTO meeting, another member replied, “Well, it’s hard to do things because there are so many kids in a grade now.”

For Klein, the statement prompted both distress and vindication. “That’s what I argued the whole time: You shouldn’t have that many kids in a grade!” she told me. And now, she felt, everybody was bearing the consequences. “I have watched something I love and value evaporate,” she said.

The final piece of the district’s reconfiguration fell into place last fall. After two years of construction, the Plains Elementary School reopened with an expanded wing and a new name: the Plains Intermediate School—now serving the district’s grades four through six. Its opening caused a shuffle in the district’s teaching ranks with most of the Plains’ previous pre-K-to-third-grade teachers transferring to Morrison-Gordon. At Morrison, many teachers felt “relieved,” said Josie Dupler, a third-grade teacher at the school. After years of struggling to manage their kids in the Plains, some of them now told Dupler, “I can teach and they get it. This is so pleasant.”

The transferred teachers turned up other surprises as well. At the Plains, they could never get enough supplies for the homecoming parade. At Morrison, the donation and volunteer slots filled up within a day. For spring break, the Plains kids used to talk about having a shopping day in Athens City or visiting the county zoo; now, the Morrison students were sharing about vacations in Jamaica and Europe. Then, when the holidays rolled around, there were the gifts from parents. Previously, the Plains teachers would “either get nothing or bless the kid’s heart who might bring in a drawing or something,” Dupler said, “but now they’re getting multiple gift cards and they’re like, Whoa, what’s this?”

The shock was also taking place in reverse. I heard about pre-K-to-third-grade teachers at East who, after absorbing new students from the Plains into their classrooms, felt overwhelmed by the rise in behavior problems and class disruptions. After moving to the Plains Intermediate, fourth-to-sixth-grade instructors from East and Morrison were experiencing something similar. One Plains teacher told me about a transferred colleague who appeared exhausted after a day of class. “Oh my God, what a group,” the colleague said, “I think I must have half of the Plains kids.”

The comment “rubbed me the wrong way,” said the Plains teacher. She felt it erased the experience of Plains educators, who had been dealing with those challenges for decades. But more important was its tone. “It was kind of like, Oh, it’s those kids,” the teacher said. Dupler, who had attended the Plains Elementary as a girl, believed that such attitudes would take time to disappear. She still lived in the Plains today, and invited me to stop by her house on a recent afternoon.

Outside in the yard, her son, Will, and a few classmates were darting around, tossing a football. A golden sun, unbroken by clouds, kept the evening chill at bay. The four friends had previously attended three different elementary schools; though they knew each other from sports, they were now attending the same school for the first time. Dupler called them inside and introduced me — first to Will, then to Keyon, Finn, and Luke.

I was curious about how moving to a new building had affected them socially. Finn spoke up first. “I couldn’t really tell the changes. It was like everybody made new friends with other schools and stuff.”

“It happened quickly,” added Keyon.

“Yeah, the first day we played basketball with kids we didn’t even know,” said Finn.

Keyon nodded. “And then we started talking.”

Their teachers were struggling with the adjustment, but the boys had already adjusted. They appeared happy to simply tap a bigger pool of friends. Around Dupler’s dining table, they kept sneaking glances outside, fidgeting, getting restless. Beyond the patio window, the sun was setting, lighting the yard in a splendid orange. I had one more question for the group. I asked if anyone was familiar with the term Rutter. Sheepishly, the four boys looked at each other and nodded.

“Wasn’t it like a last name?” said Luke. “Like a poor family or something?” Finn said he had learned about it from his parents. I asked if they heard the term at school.

“No.”

“No.”

“No.”

“Never.”

At the head of the table, Dupler’s eyes rounded in surprise. She whispered under her breath, “That’s awesome.”

With the start of this school year, the Athens City School District was settling into a new normal. When I caught up with Gibbs recently, his outlook was measured but optimistic. “We’ve done a lot,” he said, “but we still have a long way to go.” Even with the renovations and redistricting, he knew that his work was unfinished. “You can’t just change the structure of a school building and expect that in and of itself is going to create better access.”

On my last trip to Athens, I met with Rose Frech, a parent of two grade-school children in the district. Frech, who works as a social worker, recently moved to the area after living in Cleveland, where her husband had taught at a small, elite private school. “It was a $30,000-a-year kind of place,” she told me, predominantly serving the children of upper-middle-class families. “There were really beautiful things about it, but there was very little socioeconomic diversity.”

Cleveland, the second most populous city in Ohio, offered plenty of schooling options: public, private, parochial, charter, and more. But Frech and her husband noticed that few students from their school ever had the chance to mix with kids from other socioeconomic backgrounds. The school they attended — and, by extension, everyone they interacted with — had already been predetermined by their parents at the social and housing level.

In Athens, “we don’t have that option,” said Frech. “If you’re the university professor’s kid, or my dad works at the welfare department, or your parent works at the Burger King—you all go to the same school.” Rather than something to be avoided, it was one of the reasons she and her husband decided to live in Athens. “I thought that was so valuable,” she said. “It’s really one of the cool things about this area.”

A school is more than a layout of classrooms and curriculums, and an education extends beyond textbooks and test scores. As the longtime educator George Wood wrote, “What students learn in school is not what shows up on the standardized tests. More important is what they learn from the daily treatment they receive in school; this is what tells them who they are, what they can be, how their world is ordered.”

During the ’90s, Bev Drake had sent all three of her children to the Plains Elementary. Josie Dupler, the Morrison-Gordon teacher, was one of them. Today Drake lives in a house directly behind the new Plains Intermediate; a gate in her back fence opens directly to the playground. Last fall, on the first day of class, she was arranging some lawn chairs when her attention turned to a sudden burst of noise coming from the school site. It was around lunchtime. She had never heard anything like it. The voices flowed from the recess area; they were not diffuse, but concentrated. Thinking a fight may have broken out, Drake moved to her fence to look.

A mass of students — perhaps two dozen or more — had packed onto the playground’s space ball, a ten-foot, netted, ruby-red structure composed of crisscrossing tubes and bars. Drake watched, mesmerized, at all the kids balancing on top of the ball, dangling within it, hanging from every side. She looked for her grandson, Will, and found him swimming in the mix, swallowed by the shimmering hive in a tangle of limbs and hair and shoes. This wasn’t a fight. The children were playing. She continued to watch as other kids — hailing from all around the playground, all across the district — climbed on, their shouts and cheers and laughter joining together in one collective din.

This article was researched with support from New York University’s Matthew Power Literary Reporting Award.

More education stories

- Don’t Say Gay, or He, or She, or They

- The Godfather of ‘Parental Rights’ Is a Longtime Enemy of Public Schools

- The Latest Battle in the Conservative War on the American Mind