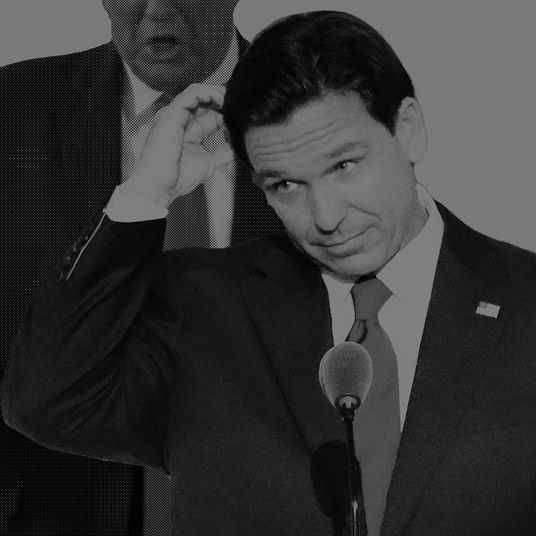

There are two stories being told in Georgia lately. In one, the state is under siege by violent left-wing militants who threaten public safety by fighting the construction of “Cop City,” an elaborate police training facility, in the forest near Atlanta. So claims a broad new RICO indictment released this week by the state’s attorney general, Chris Carr. In the indictment’s telling, 61 violent conspirators deserve prison for acts of vandalism and “intimidation.” That story appeals to state and local officials in both parties. After the indictment was unsealed, the state’s Republican governor, Brian Kemp, said his “priority” was to “keep Georgians safe, especially against out-of-state radicals that threaten the safety of our citizens and law enforcement.”

The “radicals” have their own story to tell, about the abuse of power. In their account, the RICO indictment escalates a long-running crackdown on activism. This is not the first time the state has tried to frighten people away from the movement against Cop City. Some accused face previous domestic terrorism charges. Others had been arrested in connection to earlier protests. In March, more than 150 protesters chased police from a construction site and allegedly set construction equipment on fire before blending in with the crowd at a peaceful anti–Cop City concert nearby. The state arrested dozens, including a legal observer, for domestic terrorism “even though none of the warrants accuses any of them of injuring anyone or vandalizing anything,” the Associated Press reported. Police profiled individuals for wearing muddy shoes and clothing. Months earlier, they killed an activist in alleged self-defense during an attempt to clear the forest.

The two stories are in direct conflict with each other. They cannot both be right. The RICO indictment tries to settle any debate — and it does, though not in the state’s favor. Read closely, the indictment is an artifact of political repression. In its reach it reveals the anti-democratic truth: Georgia cares more for Cop City than for civil liberties and is determined to quell dissent by whatever means it can.

The state tips its hand early in the indictment, which begins with a Wikipedia-style description of anarchism and anarchist thought. By starting here, it intends to link Defend the Atlanta Forest — which it characterizes as a group or organization as opposed to a collection of social-media accounts — to anarchism, and in turn, to violent anti-government activity. The state’s case thus begins with several leaps in logic. “Collectivism,” mutual aid, and solidarity are anarchist concepts, it claims. Because activists refer to and practice these concepts, they must be anarchists, and because they are anarchists, they want to overthrow the government, perhaps with violence. Though the indictment attempts a caveat and says that violence is present in “some anarchist beliefs,” not all, it introduces this distinction only to muddle it. To be an anarchist is to invite state scrutiny and worse.

An indictment is an unproven case. The state has implied that all 61 defendants are dangerous anarchists, and the state remains the only source for this claim. Even if the accused are all anarchists, it doesn’t mean they all conceive of anarchism in the same way or agree on the same tactics. From this inauspicious beginning, it proceeds to cite the mere dissemination of left-wing ideas as suspicious activity. Defend the Atlanta Forest recruits, it warns; people post things on the internet and hand out zines. They prepare for arrest by writing the number for a bail fund on their bodies. This is all common political activity, which Georgia seeks to punish. Even writing letters to incarcerated protesters is now evidence of a conspiracy.

The indictment further traces the Stop Cop City movement to the George Floyd uprisings and to protests over the 2020 police killing of Rayshard Brooks in Atlanta. Though the indictment itself admits that most demonstrations were peaceful, it nevertheless links vandalism to anarchism again. “The demonstrations and protests eventually ended, but an undercurrent of threatening, violent anti-police sentiment persisted with some individuals in the Atlanta area, including those that make up Defend the Atlanta Forest, and it remains as one of Defend the Atlanta Forest’s core driving motives,” it claims. Cop City was publicly announced almost a year after the Floyd protests, which makes it hard to believe that the alleged “conspiracy” could possibly stretch back that far. By tying Stop Cop City to an earlier movement against police brutality, Georgia is telling us that its motivations are punitive. Take the streets against its agents, and the state will come for you eventually.

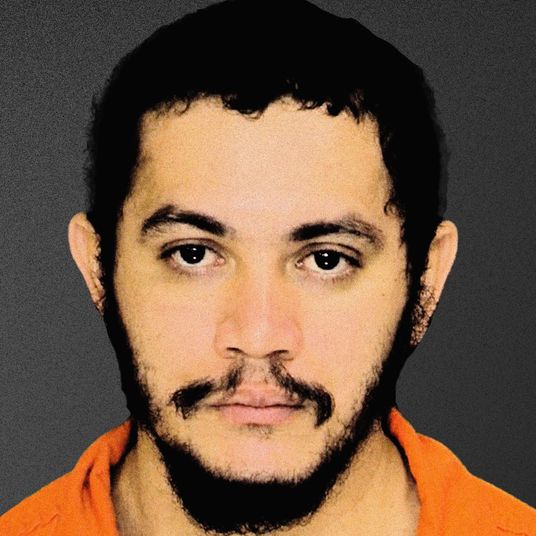

It might even kill you. The indictment mentions the fatal shooting of Manuel Paez Terán, 26, who went by Tortuguita, saying only that the activist shot a state trooper and the troopers returned fire. (There is no footage of the shooting.) Officials say that Terán previously purchased a handgun that was recovered at the scene, and that a bullet recovered from a wounded trooper matches the gun. Family and activists point to what they say is countervailing evidence: An independent autopsy released by Tortuguita’s relatives concluded that the activist was killed while seated, hands in the air. A DeKalb County autopsy found no gunpowder residue on their hands, though it said it could not reach a conclusion about the position of their hands when they were killed. The indictment does not mention, either, that troopers shot the 26-year-old Tortuguita 57 times, according to the same DeKalb County autopsy.

There is reason, then, to doubt the indictment’s claims. Even taken at face value, it veers into ludicrous territory. One charge involves an $11.91 reimbursement for glue, allegedly an “overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy.” Elsewhere, the attorney general says one man took part in a criminal enterprise because he signed his name as “ACAB.” Although the man, Geoffrey Parsons, also faces other charges, “prosecutors allege that his use of the acronym — typically an abbreviation for ‘All Cops are Bastards’ —was an ‘overt act in furtherance of the [criminal] conspiracy,’” the Appeal reported.

Carr, the attorney general, equates the act of buying glue to the act of throwing a Molotov cocktail. In a way he must, because he has a difficult task. He has to pretend that all 61 left-wing activists present a real danger to the state of Georgia. The charges might not all hold up. But the intent isn’t just to put people in prison. It’s to chill political speech and stifle activism. Carr wants to instill fear. That is how repression works. People of conscience have a duty to oppose this, whatever they think of Stop Cop City or the activists involved.

The case ought to provoke real introspection among liberals in particular. The Democratic mayor of Atlanta is among Cop City’s principal defenders. Liberal politicians are working alongside conservatives to crack down on activists and militarize the police. How distant, now, the pledges of reform, the public sympathy, the national Democrats in kente cloth. Words are easy. Anyone can criticize police brutality or attend the occasional rally. Yet values demand action, if they’re to mean anything at all. The organizers of Stop Cop City know this. To side with them now is not to justify Molotov cocktails — if anyone can prove they were used. Rather it’s to say, simply, that resistance is more than a slogan. Not a tweet. Not an item of merchandise. Resistance is a way to live. The attorney general is right, in a way, to feel threatened. Stop Cop City imagines a world where he is powerless, where solidarity is victorious and the forest lives. That world is worth fighting for, no matter the risk.